Questions for elementary school teachers: Did you feel prepared to teach when you first entered the classroom? If not, do you believe your education and training didn’t prepare you?

A recent analysis by the National Council on Teacher Quality revealed high numbers of elementary teacher candidates fail their professional licensing tests each year. An advocacy group for more rigorous teacher training, NCTQ was able to delve into scoring data made available for the first time from the Educational Testing Service, which administers the Praxis elementary content test mandated in 18 states and an option in five other states

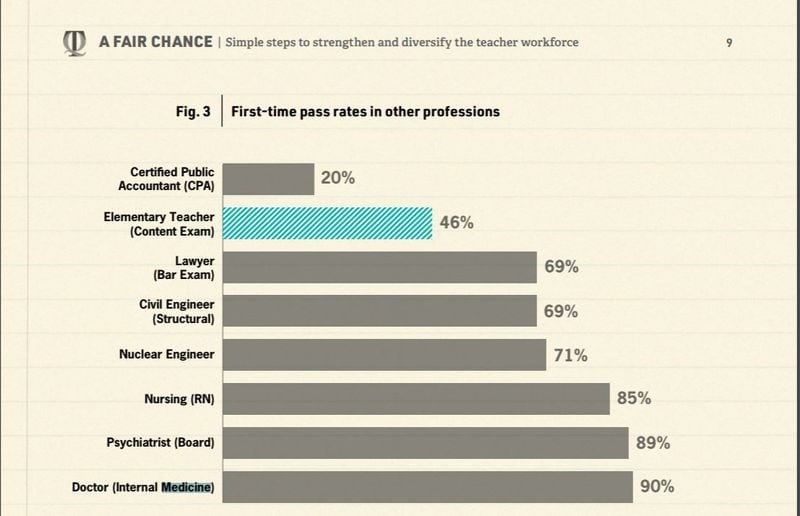

Fifty-four percent of new teachers fail their licensing exam on their first try. The pass rate is much higher in other professions requiring licensure, possibly because those fields, many of which entail longer training and offer far higher salaries, better prepare their candidates.

The report, A Fair Chance: Simple Steps to Strengthen and Diversify the Teacher Workforce, focuses on the failure rate among teachers of color, which it warns undermines the goal of increasing diversity in the workforce. The study estimates that about "8,600 candidates of color each year are likely not to qualify to teach because of low test performance."

The report states:

Already more likely to be disadvantaged by an inequitable system of K-12 education, only 38 percent of black teacher candidates and 57 percent of Hispanic teacher candidates pass the most widely used licensing test even after multiple attempts, compared to 75 percent of white candidates.

The report faults teacher preparation programs, examining the undergraduate course requirements at 817 institutions, both the general education coursework required of all students and the coursework required by the education program. The report sees a dramatic misalignment “between preparation program coursework and the content knowledge that states have determined an aspiring teacher needs to be an effective elementary teacher.”

Among its findings:

--A tiny percentage of programs (3 percent) require courses to ensure candidates gain foundational knowledge across science topics. For example, instead of directing teacher candidates to a basic chemistry course (or first requiring evidence of the candidate's knowledge of chemistry), candidates often have a choice of courses, such as how chemistry is used in art restoration or herbal medicines. Further, while some courses appear to be suitable, they are often too narrow in scope (e.g. "Lightning and Thunderstorms") to benefit a teacher who lacks a broad knowledge of science.

--Only a quarter of programs (27 percent) require sufficient coursework in mathematics.

--History, geography, and literature courses aligned with elementary standards are similarly absent from course requirements. For example, only half of all programs even require an adequate course in children's literature, in spite of the fundamental role it plays in all elementary curricula.

The report says the challenges to new teachers go beyond passing licensing exams:

This issue does not begin and end with licensing tests; even practicing teachers admit to struggling with the subject knowledge they are asked to teach. In surveys conducted by the U.S. Department of Education, two thirds of new teachers admit to not having a strong grasp of elementary subjects. Tests aside, too many teachers are left to learn on the fly, often barely covering content or omitting it altogether in their classrooms. Given that students' own ability to understand what they read depends on the breadth of the content knowledge to which they have been exposed, teachers' grasp of content knowledge is more than a matter of secondary importance. It is a top priority.

The low passage rate on licensure exams has led to calls for states to either junk or modify their tests, but NCTQ opposes that remedy:

Understand that the response to low pass rates is not to abandon tests or make them easier to pass, but to hold teacher prep programs accountable for preparing candidates in the content aligned to elementary standards.

The big question is whether passing these tests tells us anything about a person’s ability to teach effectively.

Chalkbeat examined that question in an excellent 2017 series on the relationship between certification and teacher diversity in America. Included was a profile of a well-regarded African-American teacher in Maryland who earned the highest rating possible on her evaluation but was at risk of losing her job because she could not pass the Praxis exam in math.

Tamika Peters easily passed the Praxis reading, writing, and elementary education exams, but she struggled with math and was about to take the test for the fifth time. Under the rules, Peters, who was in her second year teaching fourth grade, would have to leave if she didn’t pass – even though she had earned a master’s degree in education and completed the Baltimore City Teacher Residency training.

One issue being raised in the aftermath of the NCTQ report: While there is research linking teacher scores on licensing exams to higher student achievement gains in the classroom, there is also evidence showing students of color who have a teacher of the same race perform better.

Chalkbeat reporter Matt Barnum noted: "… research has generally shown a positive but modest link between someone's scores on standardized exams and their effectiveness as a teacher — but these exams may be less predictive for teachers of color. A study looking at Praxis scores in North Carolina found that black students performed better with a black teacher who had failed the exam than with a white teacher who passed the test."

Writing in Diverse Issues in Higher Education, Michigan State University education professor, Emery Petchauer, author of "Navigating Teacher Licensure Exams: Success and Self-Discovery on the High-Stakes Path to the Classroom," said NCTQ ignores the teachers it says it wants to help with its report:

A Fair Chance ignores every single study that tells us how aspiring teachers of color experience licensure exams. These studies show us there is much more to the story of licensure exams than NCTQ would have us believe. From aspiring teachers of color, we come to understand how taking the exams can become a racially-charged experience related to intelligence, character and test preparation. We learn how different emotional states can hinder or support performance. We get a peek into the unpreparedness of some proctors to facilitate this important exam. Learning from candidates of color, we have known long before A Fair Chance how important it is to diagnose areas of need early on and build curricular supports around those needs.

Your thoughts? (If you can only read some of these links, I would recommend the report itself, the Chalkbeat story and this great Education Week summary.)

The Ed Week piece also has good reader comments including these:

--The problem with the Praxis is that it tests memorized knowledge, not understanding of teaching practices. Yes, we as educators should have a good knowledge base. However, to expect an elementary teacher candidate to "know" everything about all subjects is not practical. A few years ago, to reach highly qualified status for ELA, I took the middle school Language Arts praxis. Some of the questions were short exerts from novels and I had to identify who the author was, or what the novel was. The only reason I knew most of these was because I had taught many of these over my career. Teaching is less about knowledge and more about interaction with students.

--The enduring challenges we have in K-12 teaching remain: "How do we get our best teachers before our students? How do we get our very best teachers before the students who truly need them? How do we dismiss our weakest teachers?"

--I also am a teacher, with 30 years of experience. I have lost count of how many colleagues struggled with passing the Praxis, have difficulty composing a coherent paragraph of writing, and are convulsed with terror when confronted with middle school level math. Often times I am embarrassed and angry when confronted with colleagues who laugh about and dismiss their struggles in a cavalier manner.

To answer your first two questions toward the end of your response, the only answer is to offer a higher rate of pay that will attract a brighter, more talented pool of candidates, away from other higher paying careers.