The vast majority of Georgia judges vying for election in May are doing so uncontested.

Only five of the 122 superior court judges on the ballot this year face challengers. For nearly 96% of incumbents, their bid to stay on the bench is a formality.

In Georgia’s appellate courts, just one judge has opposition. Justice Andrew Pinson, the youngest and newest jurist on the Georgia Supreme Court, is being challenged by former U.S. Rep. John Barrow.

The three other state Supreme Court justices and six Georgia Court of Appeals judges subject to election this year can forego the hassle of campaigning.

An overwhelming lack of opposition in judicial elections is the norm in Georgia, where judges are both appointed by the governor and elected by voters.

Atlanta litigators Eric Larson and Doug Hance say there are several factors at play. They include the nonpartisan nature of most judicial elections, the limited awareness or interest many voters have about how cases are decided, and the appointment process for judicial vacancies.

Judicial races are on the ballot, along with party primaries, on May 21.

Nonpartisanship

Almost all of Georgia’s judicial elections are nonpartisan. Some counties hold partisan elections for probate court judges, whose work includes issuing marriage and gun licenses, overseeing traffic offenses and administering wills.

They’re also held in May, when voter turnout is typically lower than in November general elections. That means they tend to fly under the radar, Larson and Hance said. They said it’s harder to challenge an incumbent in a nonpartisan election, particularly when the race takes place out of the spotlight, as voters have little to base their selection on.

“When voters look at the ballot, they only get one cue about a candidate, and that’s whether the candidate is an incumbent or not,” Hance said. “And because many voters may not be informed about judges, for various reasons, that incumbent designation makes it very difficult for challengers to defeat an incumbent in the election.”

Without party politics to rely on, it can be tricky for candidates to distinguish themselves from their opponents, Hance said. He said nonpartisan elections also typically attract less advertising money from special interest groups and don’t involve as much campaign spending as partisan races.

“What you tend to see are candidates who argue that based on their background and experience that they would be the better choice,” Hance said. “It is harder to communicate a clear message that’s going to grab the voters’ attention when you are running on a nonpartisan basis.”

Georgia’s Code of Judicial Conduct mandates impartiality. And with most of the state’s judicial elections separated from politics, it’s unusual to have a candidate declare how they would decide a specific case, Larson said.

“You don’t need that in Georgia,” he said.

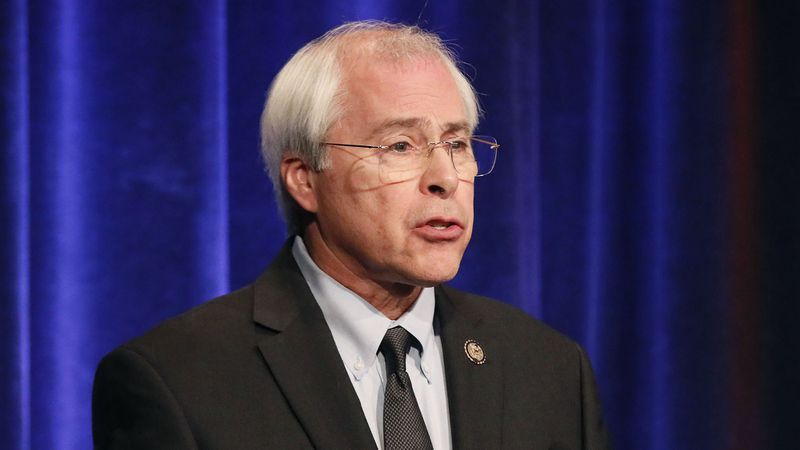

Barrow, who represented Middle Georgia for 10 years, has bucked the trend and made abortion a central issue of his campaign, stating on his election website that “we need justices on the Georgia Supreme Court who will protect the right of women and their families to make the most personal family and health care decisions they’ll ever make.”

Credit: Bob Andres/AJC

Credit: Bob Andres/AJC

Pinson, the former state solicitor general, won’t be drawn into the debate, maintaining that he approaches all cases “with an open mind and apart from personal opinion.”

“Personal preferences of individual judges should never affect how we interpret and apply our laws,” Pinson states on his campaign website.

Notoriety

It’s no surprise that no incumbent justice has lost an election since Georgia’s Supreme Court was founded in 1845, Larson said. He said most voters aren’t aware of a judge’s performance unless a case “has somehow made its way into the popular press.”

“With a lot of these judges, they’ll serve on the bench for a very long time,” he said.

The unprecedented attention on the prosecution in Fulton County of former President Donald Trump and his associates is likely why Judge Scott McAfee is being challenged in his election bid, Larson and Hance said.

McAfee is one of only two Fulton Superior Court judges in contested races this year, and the only one with two challengers. (One of McAfee’s challengers is fighting to stay in the race after she was disqualified for not living in Fulton County). A dozen of the court’s 20 judges are on the ballot.

McAfee, a former prosecutor who was appointed to the bench by Gov. Brian Kemp in late 2022, is a judge with an unusually prolific presence in the news, Hance noted.

“Challengers may think they have a better opportunity for success if voters are familiar with a judge and have formed opinions one way or the other,” he said.

Many voters don’t expect to find themselves in court and don’t pay much attention to who would preside over them if they did, Larson said. He said that’s likely another reason why few incumbent judges are challenged.

“In most instances, voters probably haven’t formed any opinion on the candidates, in which case they typically just default to the incumbent,” Larson said.

Appointments

In Georgia’s trial and appellate courts, when a judge vacates the bench before the end of their term, the governor appoints a replacement to serve a limited term until the next election at least six months after the appointment.

The governor’s choice is guided by recommendations from a state commission that reviews applicants. The process opens the door for politics to influence who serves on the state’s courts.

“When it comes to judicial elections, the most important election may be the governor’s election,” Hance said.

Barrow challenged the process in 2020, when he hoped to run for a vacant seat on the state Supreme Court that ended up being filled by appointment.

The governor’s role in judicial selection is behind Pinson’s swift ascent. Kemp appointed Pinson to the Georgia Court of Appeals in 2021 and to the state Supreme Court the following year.

Credit: Natrice Miller/AJC

Credit: Natrice Miller/AJC

Pinson told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution that he’s been preparing for his first election for more than two years. He has received just over $700,000 in campaign contributions.

“All along I have been building relationships across the bar, from all different pockets of the bar and across the state,” he said. “So, when (Barrow’s) opposition was announced, the kind of response to that was overwhelmingly positive.”

Larson said an incumbent’s ability to attract support likely plays a part in the lack of contested judicial races.

“When an incumbent judge can indicate to potential challengers that they have a significant war chest, that can be discouraging for challengers to come out against them,” he said.